Presidential elections tend to heighten uncertainty in the markets, and we’re hearing from clients looking for advice on navigating the prospect of a Trump-Biden rematch and a second term for whoever emerges victorious in November. The allure of altering investment plans during uncertain times can be tempting, fueled by the promise of potential gains or the fear of impending losses. However, history implies that inaction may be the best course of action to take.

In the frenzy of an election year, it’s easy for investors to be focused on political pronouncements and speculate on their effect on the economy and the market. And while there is nothing wrong with wanting your candidate to win, in the end, Presidents have far less impact on the economy than investors give them credit for. Economic growth, which ultimately drives stock market growth, are impacted by a variety of variables, few of which Presidents have any control over.

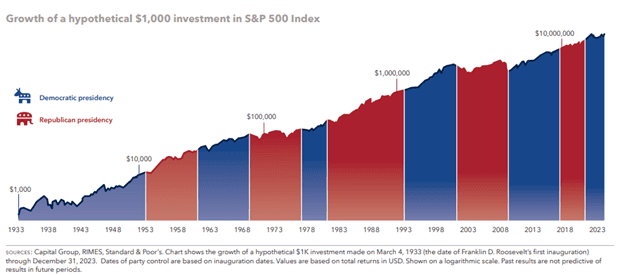

Recent history helps illustrate the point. During President Obama’s eight years in office, the Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Index rose an average of 12.77% annually. In President Trump’s four years, it grew an average of 13.6% annually. Thus far under President Biden, the market has returned an average annual return of 16.4%.* Looking back further illustrates similar trends.

The story is unchanged when we include the political make up of Congress. Since 1933, the “least good” outcome has been when Congress is controlled by the opposite party of the President. During those periods, the S&P 500 averaged a solid 7.4% annual return. In all other configurations, annual market returns have averaged in the double digits.

Despite the comfort of looking at history, the messaging around the election cycle only gets more intense and increases uncertainty and fear. Trying to stay invested amidst all the negative messaging is difficult. In 2020, the investment research firm Morningstar studied money flowing into equity funds and money market funds in an election year and the year following the election.

During the period 1992-2020, an election year saw investors shift $76 billion into equity funds and $176 billion into money market funds. In the year following the election, the flows reversed, with $168 billion moving into equity funds and $36 billion into money market funds. Regardless of which party prevails, investors prefer staying on the sidelines until they know the president is elected.

Yet, from an investment standpoint, avoiding risk until the election is over generally produced the lowest returns. In a study done by Capital Group, they analyzed returns over the last 22 election cycles to compare three hypothetical investment approaches: being fully invested in equities, making monthly contributions to an equity portfolio, or staying in cash until a year after the election and then investing.

Of the 22 elections – dating back to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 – the investor who stayed on the sideline had the worst outcome 16 times and only had the best outcome three times. On the other hand, investors who remained invested or were disciplined in contributing regularly to their portfolios came out ahead on the vast majority of occasions.

While history seems to favor the disciplined investor, the attraction of identifying “obvious” beneficiaries of a policy change, for instance, is a powerful draw. However, campaign promises don’t necessarily turn into policy decisions and obvious winners seldom turn out to be so. . Or the performance of a company’s stock may not react as we’d anticipate with speculators rushing in or out of industries or firms they perceive to be in favor.

Instead, it is the economic context, not the political one, that we need to remain focused on. It is a task made more difficult during election cycles when all economic news becomes politicized, mixed with increased negative messaging from the candidates and the never-ending drone of the news cycle. All this pushes investors toward the feeling of wanting to “do something.” As we’ve said, sometimes the correct thing to do, and the hardest thing to do, is nothing at all.

Recent Comments